Samhita Mukhopadhyay wasn’t expecting shame to come from a photo. The longtime feminist writer and former Teen Vogue editor had just moderated a panel at a media conference. She was dressed in a skirt and printed top she felt good in—until she saw a candid image someone had posted online. “It was devastating,” she told Newsweek.

Mukhopadhyay took Mounjaro, an antidiabetic medication also used for weight loss, and saw dramatic results—losing 15 percent of her body weight over 18 months. She was feeling physically better, sleeping more soundly and even considering a wardrobe overhaul. But the cost of the drug forced her to stop.

Peter Dazeley/Getty

“I knew better,” she said. “As a feminist writer and committed proponent of body positivity, I’d spent years trying to love my body at any size. And yet, here I was, agonizing over a picture of myself.”

That contradiction, she said, was the real heartbreak—not just for her, but for the women who long-embraced the body positivity messaging themselves. “Taking something for weight loss made me feel like I was being vain, that I didn’t have the willpower to lose weight, eat better or exercise,” she said. “It felt like a violation of an unspoken norm.”

Samhita Mukhopadhyay

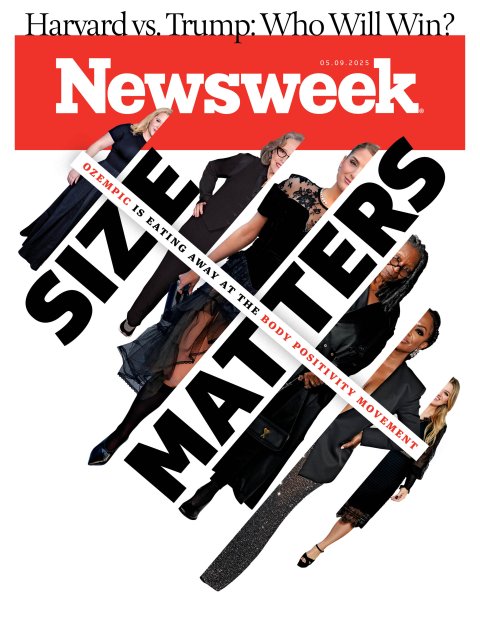

Hollywood’s Open Secret

In recent years, Mounjaro and similar GLP-1 drugs like Wegovy, Ozempic and Zepbound have redefined how America thinks—and talks—about weight. What began as a diabetes treatment has become a billion-dollar industry fueled by off-label use, celebrity whispers and red-carpet transformations.

As the 2025 Hollywood awards season kicked off with the Golden Globes in January, so too did another round of jokes, speculation and sponsorships linking the industry to the use of GLP-1 medications for weight loss by A-list celebrities. Comedian Nikki Glaser, host of the Globes, dove right in at the start of her opening monologue: “Good evening, and welcome to the 82nd Golden Globes—Ozempic’s biggest night,” she began.

Sonja Flemming/CBS/Getty

What may be the most effective pharmaceutical marketing campaign in history didn’t cost a dollar. Starting in mid-2022, celebrities and influencers began posting about their weight loss journeys using GLP-1 drugs, drawing millions of views on social media. The result was free publicity for Novo Nordisk, the Danish pharmaceutical giant behind Ozempic and Wegovy. (Mounjaro and Zepbound are manufactured by Eli Lilly, an American competitor to Novo.)

In September 2022, Variety reported that A-listers were quietly sharing their experiences in encrypted Signal chats. The drug’s popularity became such a phenomenon that Town & Country called it the hottest topic of conversation in L.A. Outside Hollywood, telehealth startups and boutique clinics capitalized on the growing demand, offering prescriptions to those without diabetes or clinical obesity—provided they could afford it.

By the time the 2025 awards season arrived, Hollywood’s connection to GLP-1s was too loud to ignore. Coverage of the SAG Awards labeled it “the Ozempic carpet,” with headlines marveling at the dramatic slimdowns of some stars. No one was safe from accusations. Despite being forced to defend her weight weeks before, it was speculated Ariana Grande had turned to GLP-1s, while Demi Moore was also linked to them, though she recently told People magazine her figure is the result of listening to her body and avoiding meat and eggs. “I think a big part of wellness is really inside out,” she added.

Iuliia Burmistrova/Getty

Kelly Clarkson, meanwhile, admitted to taking medication to help with weight loss, but said: “Everybody thinks it’s Ozempic. It’s not. It’s something else. But it’s something that aids in helping break down the sugar. Obviously, my body doesn’t do it right.”

Other stars like actress Kathy Bates proudly acknowledged taking “the shot.” She joined a growing list of celebrities—including Whoopi Goldberg, Oprah Winfrey, Amy Schumer, Meghan Trainor and Kandi Burruss—who have spoken openly about turning to GLP-1 medications in their weight loss journeys after years of public scrutiny.

Comedian Schumer said she’s “loving being on Mounjaro,” while singer Trainor credited her transformation after her second pregnancy to “huge lifestyle changes,” and a “shoutout to Mounjaro.” Musician Burruss, known as Kandi, admitted: “I saw so many people who were trying it and losing weight. So I was like, ‘OK, I’m going to try this.'”

MICHAEL TRAN/AFP/Getty

This explosion of exposure has translated directly to sales. In 2021, Ozempic didn’t even break into the top 20 of the bestselling drugs worldwide. By 2024, it would rise to second place, with Novo Nordisk reporting a 25 percent jump in annual revenue to $40.6 billion. The company also announced it was expanding manufacturing capacity to meet soaring demand, including a $4.1 billion investment in a new U.S. facility and the $11 billion acquisition of three Catalent plants in New Jersey.

The Price of Thinness

The rise of Ozempic, Mounjaro and Wegovy has reframed weight loss as a clinical intervention—but one still largely reserved for those with deep pockets, especially since users report the weight often comes right back on as soon as they stop taking the drugs. With prices often ranging between $1,000 and $1,400 per month and inconsistent insurance coverage, these medications are far from universally accessible.

“Ethical concerns around GLP-1 drugs often center on access and affordability,” said Dr. Robert Klitzman, a professor of psychiatry and bioethics at Columbia University. “The medications are expensive, and insurance coverage varies widely. As a result, they’re often only accessible to people with higher incomes or strong health insurance.”

State Medicaid programs have already felt the pressure. Spending on GLP-1 drugs jumped from $577.3 million in 2019 to $3.9 billion in 2023, with projections indicating growth is nowhere close to plateauing. Some states have started considering whether to restrict access, citing escalating costs.

Yet in a nation where 42 percent of adults live with obesity—a rate that has nearly doubled since the 1980s—the arrival of a drug that actually works was hard to ignore. In 2013, the American Medical Association officially classified obesity as a disease, recognizing the condition’s complexity and its contribution to other chronic illnesses.

Amy Sussman/Getty

GLP-1 medications seemed to offer exactly what had been missing for decades: a treatment that not only helped patients lose weight, but also improved other key health markers. Clinical trials show that users can shed 15 to 25 percent of their body weight, along with seeing better blood sugar levels, lower blood pressure and improved cardiovascular health.

The promise of GLP-1s has even drawn high-level political attention. Elon Musk—the world’s richest man and a constant presence in President Donald Trump’s White House—has publicly called for expanded access on public health grounds. “Nothing would do more to improve the health, lifespan and quality of life for Americans than making GLP inhibitors super low cost to the public,” he wrote on X. Musk has also acknowledged using Wegovy himself.

Eric McCandless/Disney/Getty

Klitzman, the Columbia bioethicist, cautioned that while the drugs are promising, broad adoption could financially destabilize health systems.

“These drugs help over 50 percent of people lose up to 25 percent of their body weight,” he said. “But they cost around $12,000 a year. If two-thirds of Americans needed them, it would bankrupt the health care system.”

Robert F. Kennedy Jr., secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, dismissed the drugs outright. “They’re counting on selling it to Americans because we’re so stupid and so addicted to drugs,” he told Fox News in October, before the incoming administration shelved a $35 billion Biden-administration plan to expand Medicare and Medicaid coverage for GLP-1 drugs for weight loss.

Andrew Harnik/Getty

Health economists have also shared concerns about long-term affordability, even if these drugs prevent diabetes or heart disease. “The short-term cost is still huge,” Dr. Cynthia Cox, vice president at KFF (formerly Kaiser Family Foundation) told Newsweek. “$1,000 a month per person is a massive outlay.”

Shame, Access and the New Inequality

According to a KFF analysis, the list price of Ozempic in the United States is $936 per month, more than five times the cost in Japan, where it sells for $169—the second-highest price among the countries studied. Wegovy, which shares the same active ingredient as Ozempic, is roughly four times as expensive in the U.S. ($1,349) compared to Germany ($328).

But even among those who can afford GLP-1 medications, few escape the double bind that now defines weight loss: the pressure to change and the scrutiny that follows when they do.

Many public figures who have struggled with weight and identity now feel pressure from both sides. Influencers who once championed “fat acceptance” are now subject to backlash from the very communities they helped build. Plus-sized model Ella Halikas, who took Ozempic to manage polycystic ovary syndrome, or PCOS, admitted: “I was worried about disappointing my followers.”

Amy Graves/Getty Images for Forever 21

Rosey Blair, another plus-size content creator, wrote that she was accused of being “ableist and fatphobic” for publicly celebrating the mobility she gained from taking Mounjaro.

Dr. Chika Anekwe, an obesity medicine specialist at Massachusetts General Hospital, explained to Newsweek that stigma is often rooted in cultural ideas about willpower. “People don’t usually call insulin or cholesterol-lowering drugs ‘cheating,'” she said. “But weight loss medications still face scrutiny because obesity is not accepted as a legitimate medical condition. That has to change.”

Klitzman said the issue isn’t just about cost or personal choices. “It’s also driven by poor access to healthy food, lack of exercise, income inequality and nonstop junk food marketing,” he said. He added that while GLP-1 drugs work by curbing appetite, they don’t address deeper problems. “You can’t solve obesity just by handing out prescriptions,” he said. “If policymakers start seeing these drugs as a silver bullet, there’s a real danger they’ll pull back on funding for prevention—like nutrition programs, access to healthy foods or education around physical activity.”

Not Just Aesthetics

Still, the cultural conversation continues to orbit around aesthetics. “These drugs don’t exist in a neutral landscape,” said journalist Virginia Sole-Smith on the Burnt Toast podcast, which focuses on diet culture. “They exist in a culture where thinness still equals goodness.”

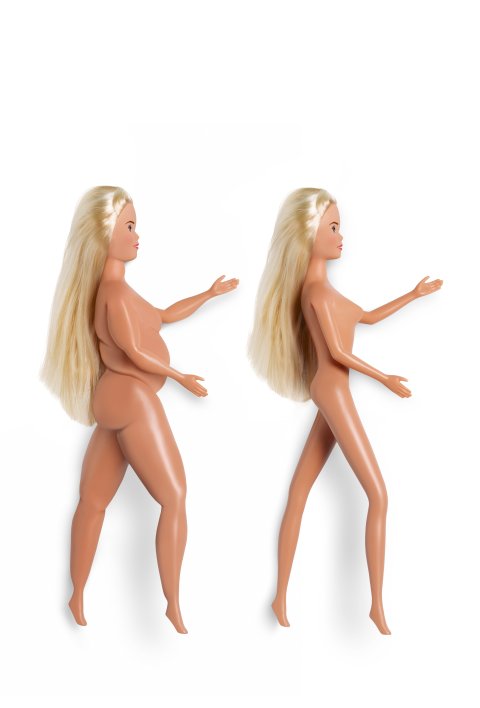

For people who once found refuge in body positivity’s message of self-acceptance, that reemergence of a single ideal feels regressive.

The body positivity movement had its own strange journey from fringe topic to mainstream acceptance to corporatized sloganeering. Rooted in 1960s fat activism, it began as a demand for dignity and systemic change: access to medical care, protection from discrimination, representation in media. Over time, driven by advertising campaigns like Dove’s “Real Beauty,” Photoshop-free ads and soft-lit models with stretch marks, its message softened into palatable slogans—encouraging self-love while often ignoring deeper inequalities.

gorodenkoff/Getty

“This rebranding of body politics allowed corporations to position themselves as champions of inclusion without making meaningful changes,” writer Amanda Mull argued in her 2018 Vox essay “Body Positivity Is a Scam.”

That kind of defiance underscores a broader tension. As GLP-1 drugs become more visible—and increasingly associated with thin, wealthy celebrities—many outside that privileged circle are left grappling with a difficult question: not just should I take it, but can I take it without feeling judged?

Editor Mukhopadhyay is uniquely positioned in the debate—both as a journalist and someone who took the drug. “I had a lot of anxiety about talking about it and telling people I was taking them,” she said. “There was judgment from the body positivity side and judgment from people who still think using drugs for weight loss is vain.”

Willie B. Thomas/Getty

And yet, influencers aren’t just people—they’re public figures with brands, sponsors and audience expectations. “There’s this idea that you can’t be too thin or too fat,” she said. “Where do you find the balance?”

Klitzman emphasized that individual choices and so-called miracle drugs alone won’t solve the obesity epidemic. “We need a comprehensive, systemic approach,” he said. “That means everyone—doctors, patients, policymakers, insurers, food companies… the environment that fosters obesity needs to change. Otherwise, we’re just treating symptoms.”

And perhaps, as Mukhopadhyay said, the internet is not the place to resolve it. “Social media can be triggering,” she said. “And it might not be the best place to seek validation for how you feel about your body.”

She believes the better question is what followers owe themselves. “If someone’s decision to change triggers you…ask yourself why. Influencers are not responsible for your emotional well-being.”